Local Data Persistence and Notification Center

Michael Lin

Table of Contents

Local Data Storage Options

Last week we talked about Cloud Firestore, an NoSQL cloud database that can store and sync data from your app, and we used it in MP3 to develop an social app where one can create events and share details with other users. But that was a big jump - not always do we want to store our data in a remote server. In some cases, storing data locally will be much more effective and convenient.

A classic example of where we would want to use local data storage is with the user’s settings. Assuming we don’t care about syncing settings between devices, there’s no point of uploading them to a remote server. Furthermore, when the data is too large to store on a server, local storage is our only option.

Today we will introduce two new frameworks in the iOS SDK: FileManager and UserDefaults.

File Manager

The first local storage option that we will look at is the file system. Similar to most desktop OS, files in iOS are organized into directories. In MP2, we used a pokemon.json file from the app’s bundle folder to generate an array of Pokemon objects.

guard let url = Bundle.main.url(forResource: "pokemons",

withExtension: "json") else { ... }

guard let jsonData = try? Data(contentsOf: url) as Data else { ... }

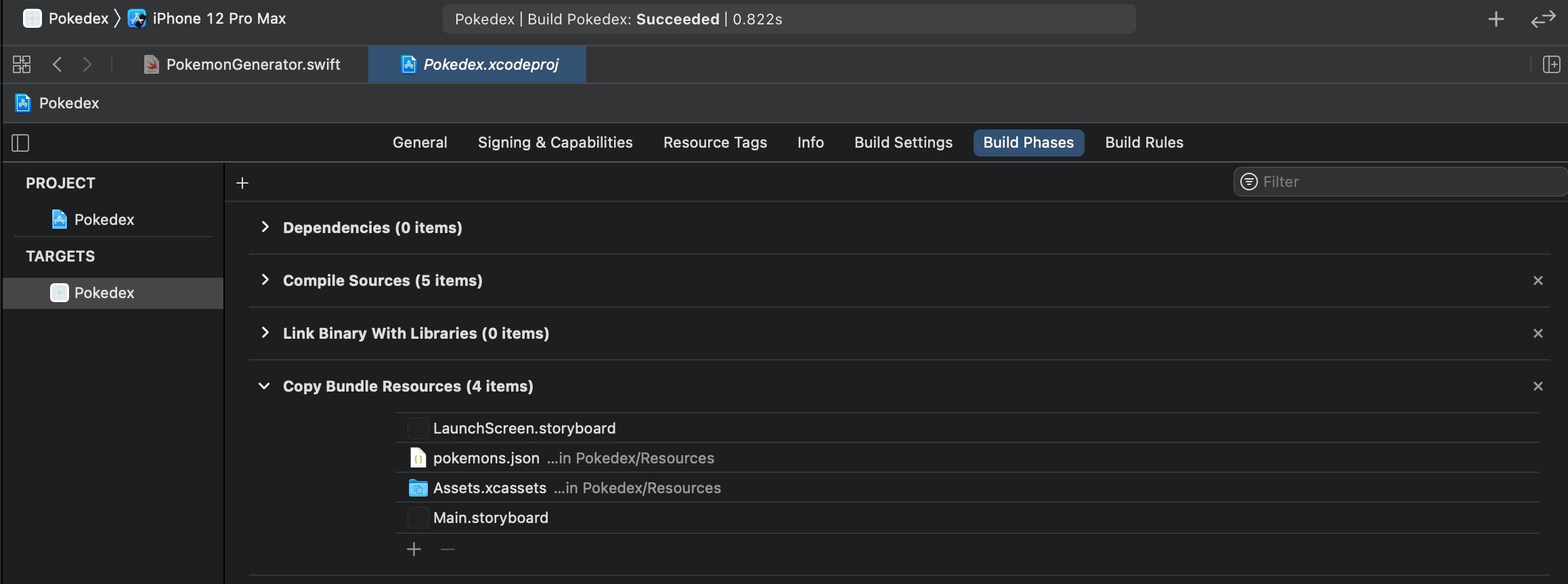

When Xcode builds the app, it builds it into a bundle object that contains all the binaries, resources, and extra files in the project. This organizes the app into a well-defined package, so that when people download it from the App Store, they only need to download the (main) bundle. And as we saw in MP2, with bundles, we can access its content without knowing the structure, which makes it a great choice for static resources such as images and our pokemon.json.

However, bundles are read only and are deleted with the app. Therefore, if we are looking to write something back to the file system, we will have to interact with other directories as well.

Luckily, this turns out to be not too difficult, we just have to use the FileManager APIs.

guard let url = FileManager.default.urls(for: .documentDirectory, in: .userDomainMask)

.first!.appendingPathComponent("pokemon.json") else { ... }

guard let jsonData = try? Data(contentsOf: url) else { ... }

The first line retrieves a URL from the document directory in the user domain (~/). Notice that the method takes in two enum arguments specifying the directory and the domain mask. Compared to a hardcoded path string, this method standardizes the app’s storage structure while maintaining a certain degree of flexibility.

Writing to the url is also straightforward:

try jsonData.write(to: url)

// Error handling

User Defaults

Being able to manage files is great, but sometimes, it can be an overkill too. What if we just want to keep a few settings or flags (like whether the app is launched for the first time)?

This is where UserDefaults comes in. It enables us to store key-value pairs to the user’s internal database. For example, you can store the default layout for your Pokemon collection view with just one line of code.

UserDefaults.standard.set("grid", forKey: "pokemonLayout")

and to get the value:

let layoutRaw = NSUserDefaults.standard.string(forKey: "pokemonLayout") ?? "row"

let layout = PokemonLayout(rawValue: layoutRaw)

Notice that the getter returns an optional string, so we can use the nil-coalescing operator ?? to provide a default value.

Behind the scene, your data is persisted through a .plist file in the app’s bundle (so it also gets deleted with the app!). This means that User Defaults can only store Data, String, Number, Date, Array,Dictionary, because these are the types allowed in a property list. Though you can typically store other types by converting them into an instance of Data.

Keychain

As a side note, you should never store passwords or other sensitive information in User Defaults. The correct way to do that is through the Keychain Service.

Notification Center

Recall that in MP2, when the Pokemon collection view needs data or layout information, it will fetch that information from the PokedexVC, which is the delegate of that collection view and conforms to UICollectionViewDataSource and UICollectionViewDelegateFlowLayout protocols.

The delegation pattern is a powerful design for any one-way communication between the two objects. However, it becomes limited when multi-way communication is needed.

Imagine the following scenario in MP3: the underlying User struct in AuthManager.shared.currentUser has just been updated by Firebase. Then not only do we want to update the .currentUser property, we want all the controllers that are using this property to be notified, so that they can refresh the UI.

So how do we do this? Our first thought could be to create something like this in the AuthManager.

var delegates: [AuthManagerDelegate] = []

and in the protocol, we add a userDidChange method

protocol AuthManagerDelegate {

func authManager(_ manager: AuthManager, userDidChange user: User)

}

so when we receive the update from Firebase, we iterate through the array of delegates

delegates.forEach { $0.authManager(self, userDidChange: user) }

But hold on, all the elements in the delegates array are going to be retained with a strong reference. So it will keep everything alive as long as AuthManager.shares is in memory. Since AuthManger.shared will persist throughout the App’s lifecycle, those view controllers will never be released.

Undeterred, we will attempt to fix this issue by implementing a custom wrapper class

var delegates: [Weak<AuthManagerDelegate>]

class Weak<T: AnyObject> {

weak var val: T?

init (val: T) { self.val = val }

}

and use a compact map to remove any deallocated delegates

delegates.compactMap({ $0.val }).forEach {

$0.authManager(self, userDidChange: user)

}

But even so, eventually, the delegates array will be littered with unuseable pointers and we will have to iterate through all of them every time we call a delegate method.

This problem is inherently difficult to solve with delegate. That’s why we need something else to handle this task, and the most common one is the NotificationCenter.

Shipped with the Foundation framework, NotificationCenter is a centralized mechanism for dispatching notification to registered observers.

We will start by add an observer to receive a notification, along with selector that’s gonna be the handler of the notification.

NotificationCenter.default.addObserver(self, selector: selector(didUpdateUser(_:)),

name: Notification.Name("FIRDidUpdateUser"), object: nil)

Whenever we get a user update from the Firebase, we will post a notification with the same name in the AuthManager.

NotificationCenter.default.post(name: Notification.Name("FIRDidUpdateUser"),

object: nil)

This will be delivered to every object that observes the notification.

Notice that in the example we had to type in “FIRDidUpdateUser” twice. A more robust way to do it is to just define it in Notification.Name with an extension.

extension Notification.Name {

static let FIRDidUpdateUser = Notification.Name("FIRDidUpdateUser")

}

then our post line will look like this

NotificationCenter.default.post(name: .FIRDidUpdateUser, object: nil)